-40%

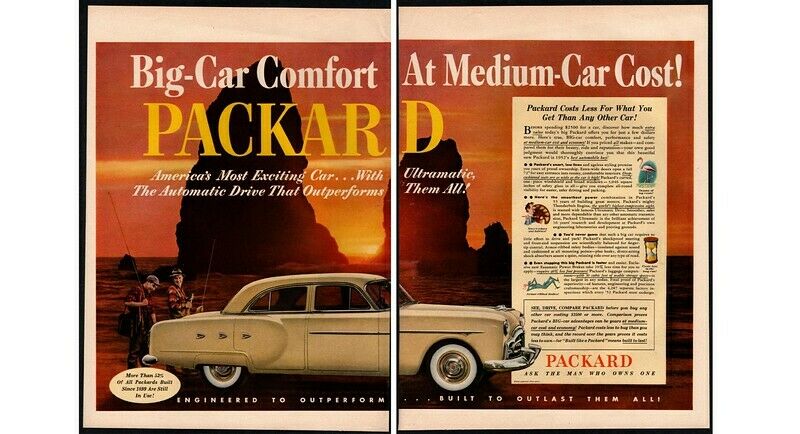

1949 PACKARD BROCHURE ULTRAMATIC DRIVE

$ 6.06

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

1949 PACKARD BROCHURE ULTRAMATIC DRIVE 16 pagesThe last word in automatic, no-shift control!

Mint condition with lots of underlining in fountain pen ink.

New in principle… new in performance!

.- there’s never been anything like PACKARD Ultramatic Drive

Packard Ultramatic Drive is now standard equipment on America’s most luxurious motor car… the 160-horsepower Packard Custom.

As production of this precision-built unit gradually attains higher volume, Packard Ultramatic Drive will be offered on other models in the Packard line as optional equipment, at extra cost.

Packard Ultramatic Drive goes beyond all earlier types of automatic drives in performance.

And the reason is simple… It’s because this new drive sensation – born of a 16-year Packard development and test program – goes beyond the others in basic principles.

Packard Ultramatic Drive is the last word in simplicity… in smoothness… and in all-range, all-driving-conditions efficiency.

It gives you more responsive, more flexible, more positive car control than you’ve ever enjoyed before.

How Packard Ultramatic Drive measures up to these sweeping claims is clearly and briefly told in the pages that follow.

How Packard Ultramatic Drives compares with earlier drives… in basic principles

Patents on automatic drive units date back as early as 1904.

But it was not until the late 1930’s that modern automatic drives were offered in volume, to the motoring public.

Of today’s three most widely used passenger car drive designs, two were introduced in prewar years and are often described as “step-type” drives.

The third, introduced after the war, might be described as a “curve-type” drive.

These simple diagrams show you how those drives compare, in principle, with Packard Ultramatic Drive.

DRIVE “A”:

Introduced in 1939.

Employed a fluid coupling plus conventional clutch, operated by a foot pedal.

Two-speed semi-automatic transmission provided four forward speeds.

Clutch pedal and gear shift lever had to be used to shift from low-range to high-range, but no shifting was required in normal driving.

In either range, it was necessary to release pressure on the accelerator in order to change gear ratios.

DRIVE “B”:

Introduced in 1940.

Employed a fluid coupling plus four-speed automatic transmission.

No clutch pedal.

The fluid coupling transmitted the engine’s “twisting” effort ( torque ) directly to the transmission, where it was stepped up or down through a system of planetary gears.

Gearshifting was performed entirely by the transmission.

DRIVE “C”:

Introduced in 1948.

Employed a hydraulic torque converter, which provides an infinite range of “gear ratios” without the use of gears, and thus eliminates need for an automatic transmission.

Two-speed transmission offered a choice of low range or high range operation.

No clutch pedal.

In this design, the car was driven at all times through the torque converter – at cruising speeds as well as during acceleration.

PACKARD ULTRAMATIC DRIVE:

Introduced in 1949.

Employs an advanced design torque converter for smooth, rapid acceleration – and solid mechanical drive offer slippage-free cruising.

Dual-range transmission offers a choice of low range or high range operation – with torque converter acceleration, and solid mechanical-drive cruising, in each range.

No clutch pedal.

Automatic controls perform the switch from torque converter to mechanical drive.

How Packard Ultramatic Drive compares with earlier drives……in performance

SIMPLICITY:

SMOOTHNESS:

THRIFTY EFFICIENCY:

QUIETNESS:

ALL-RANGE SAFETY:

MORE RESPONSIVE CONTROL:

MORE POSITIVE CONTROL:

MORE FLEXIBLE CONTROL:

X-Ray view of the advanced features of Packard Ultramatic Drive

Automatic controls.

Automatic, yes – but the never try to “out-smart” the driver.

If his foot pressure on the accelerator is light, the controls will switch from torque converter to mechanical drive at 15 miles per hour.

If the pressure on the accelerator is heavy, the controls will switch from torque converter to mechanical drive at 55 miles per hour.

If pressure on accelerator is released momentarily, at any point between 15 and 55 miles an hour, the controls will switch immediately from torque converter to mechanical drive.

If driver “tramps down”, at any cruising speed below 50 miles an hour, the controls will switch instantly from mechanical drive to torque converter for rapid acceleration.

(At cruising speeds above 50 miles an hour, direct drive acceleration is superior to torque converter acceleration.)

Selector lever.

Settings for “Park”, “Neutral”, “High-Range”, “Low Range”, and “Reverse”.

Advanced design torque converter.

Provides an infinite range of “gear ratios” without gears.

Multiplies engine torque as much as two and one-third times during acceleration.

Used only for acceleration, when varying degrees of slippage are desirable.

Not used for cruising.

Dual-range transmission.

Gives driver a choice of low range or high range operation – with torque-converter acceleration and solid mechanical-drive cruising in each range.

(Low range is needed only for climbing or descending extreme grades.)

Transmission also includes reverse gear.

Mechanical direct drive.

New-type clutch operates completely submerged in oil.

Engagement is smooth and silent.

Prevents slippage at cruising speeds.

Provides smooth, gradual engine braking effort, down to speed of 15 miles an hour.

How to understand the torque converter principle… in 4 easy lessons

.1

The torque converter, in shape, resembles a fluid coupling.

Two bowl-shaped members, whose inner sides are lined with vanes, face each other in an oil-filled chamber.

One member, the pump (or driver), rotated by the engine, directs the oil against the vanes of the facing member, called the turbine ( or follower ).

.2

To change the fluid coupling into a torque converter – so as to multiply the “twisting effort”* or torque of the engine – a reactor unit is placed between the pump (or driver), and the turbine (or follower).

.3

The vanes of the reactor pick up the flow of oil from the turbine (or follower), and “curve” the oil’s direction of flow into a forward direction to step up its velocity to assist the pump (or driver).

.4

The reactor assists the pump (or driver ) in making the oil “work harder” while it is traveling through the turbine ( or follower ).

By doing so, it multiplies the engine torque*.

.* In Packard Ultramatic Drive this “twisting effort” is multiplied approximately two and one-third times.

HISTORICAL NOTE:

The torque converter principle was put to work as early as 1905, in a marine application.

Later it was used in industrial and heavy vehicle applications.

Background story of Packard Ultramatic Drive

Now… you’re ready to go for a ride with Packard Ultramatic Drive

And what about service needs?

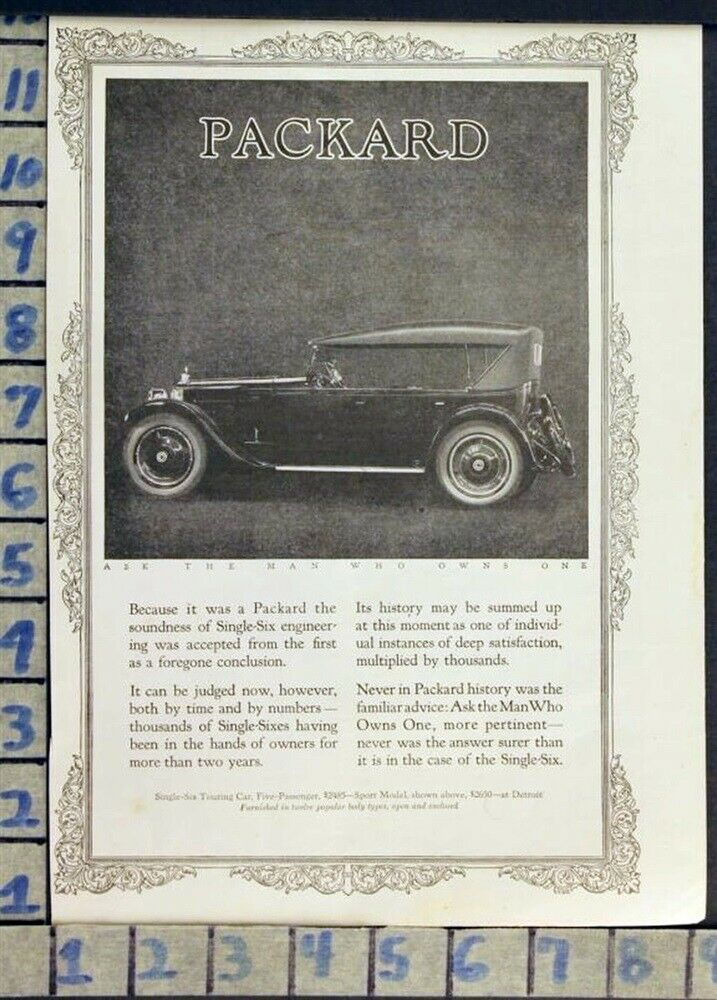

All these brochures were found in my uncle's / grandmother's attic.

My uncle began collecting these from dealers about age 13.

Combined items reduces total shipping cost. I will combine into a 1 package weight shipping.

Powered by

eBay Turbo Lister

The free listing tool. List your items fast and easy and manage your active items.